Nekros; or, The Poetics of Biopolitics

|

Eugene Thacker

June 17, 2013  DOI: 10.13095/uzh.fsw.fb.20 DOI: 10.13095/uzh.fsw.fb.20

editorial review CC BY 4.0 |

print comment |

Keywords:

Tag error: <txp:tru_tags_from_article /> -> Textpattern Notice: tru_tags_from_article tag is not registered while parsing form article_keywords on page default

textpattern/lib/txplib_publish.php:563 trigger_error()

textpattern/lib/txplib_publish.php:409 processTags()

textpattern/publish/taghandlers.php(4301) : eval()'d code:2 parse()

textpattern/publish/taghandlers.php:4301 eval()

php()

textpattern/vendors/Textpattern/Tag/Registry.php:138 call_user_func()

textpattern/lib/txplib_publish.php:559 Textpattern\Tag\Registry->process()

textpattern/lib/txplib_publish.php:409 processTags()

textpattern/plugins/tru_tags/tru_tags.php:121 parse()

tru_tags_if_has_tags()Bio-politics. A question: what is the "bio" of biopolitics? Contemporary theories of biopolitics often emphasize medicine and public health, political economy and governmentality, or the philosophical and rhetorical dimensions. But if biopolitics is, in Foucault's terms, that point at which "power takes hold of life," the moment in which "biological existence was reflected in political existence," then it follows that any theory of biopolitics will also have to interrogate the morphologies of the concept of "life" just as much as the mutations in power. [1]

It is remarkable how the concept of "life itself" has remained a horizon for much biopolitical thinking. [2] There is, for instance, the naïve position, in which one presumes something called "life" that pre-exists or exists outside of politics, which is then co-opted into specific power relations (e.g. political economy, public health, statistics and demographics). The problem with this approach is that it forces one to accept a concept of life that is either excessively vague (life-as-experience) or reductive (life as a molecule, life as data). The presumption of a pre-existent life also puts one in the dubious position of arguing for a protectionism regarding life, effectively making the removal of politics from life the goal of the critique. While we may disregard this position as naïve, it is important to note how it surreptitiously haunts contemporary critiques of medicine and health care, from "big pharma" to the ongoing debates over public health security and bioterrorism.

The opposite of this is the cynical position, in which one assumes that there is no extra-political, essential concept of "life itself" that is then co-opted by politics or recuperated in power relations. Life is always already political, not only at the literal level of medicine, but also in the way subjects are interpolated at the level of social, economic, and political life. Life is a concept that is not only constructed within scientific discourse, but equally within political discourse—even when that discourse articulates an "outside" called natural law, human rights, or bare life. As a more sophisticated form of critique, the problem with the cynical approach is that it can end up leveraging critique on behalf of an empty concept. Since there is no pre-existent life that is co-opted by power, one is left with either dispensing with the concept altogether—a difficult task, since the concept of life remains politically operative in a variety of contexts—or one argues for a renewed concept of life that has yet to be envisioned—in effect producing a concept of pre-existent life similar to the one in the naïve position.

"Zombi 2" (dir. Lucio Fulci, 1979)

The Problem With Multiplicities. Perhaps what life is, or how it is defined, is less important than the question of whether something called "life" comes under question at all in biopolitical theories—and one that is also not simply an empty yet functional shell. Michel Foucault's Collège de France lectures offer several ways of addressing this dilemma. In Foucault's 1978 course, biopolitics is often characterized in terms of multiplicity—but the particular multiplicity of the collective, aggregate life that is the population. Foucault mentions three examples of epidemics as correlated to particular forms of power. In the Middle Ages, leprosy is aligned with sovereignty, and its ritual dividing practices and exclusion. The example of plague during the 16th and 17th centuries is, for Foucault, aligned with disciplinary power and its practices of inclusion and ordering. Finally, Foucault mentions smallpox and vaccination as an example of a third type of power, the apparatus of security, which "pulls back" and carefully observes the outcome of an event, so as to selectively intervene. It is from this third type of epidemic that Foucault isolates a power that stitches together medicine, politics, and a concept of "population"—that is, an awareness of a novel object of power that is defined at once by its multiplicity, its temporal dynamics, and its statistical fluctuations. What emerges, Foucault argues, is a form of power that operates at the level of highly-specified perturbations, one that intervenes at the level of the flux and flow, the manifold circulations, that is the population itself. "Circulation understood in the general sense as displacement, as exchange, as contact, as form of dispersion, and as form of distribution—the problem presented is: how can things be ordered such that this circulates or does not circulate?" [3]

Biopolitics is unique in Foucault's analysis because it expresses power as a problem of managing circulations and flows—something like biopolitical flow. It makes use of informatic methods, including statistics, demographics, and public health records, to insert a global knowledge into the probability of local events; it identifies and reacts to potential threats based on a whole political economy of the regulation of state forces; and, instead of a dichotomy between the permitted and forbidden, it calculates averages and norms upon which discrete and targeted interventions can be carried out. In a striking turn of phrase, Foucault suggests that, in this correlation between a distributed power and a distributed life, the central issue becomes "the problem of multiplicities" (le problème des multiplicités). [4] In this sense, biopolitics "is addressed to a multiplicity of people, not to the extent that they are nothing more than their individual bodies, but to the extent that they form, on the contrary, a global mass that is affected by overall processes characteristic of birth, death, production, illness, and so on." [5]

If we follow Foucault's leads here, then the "bio" of biopolitics has to be understood as a concern over the governance of "life itself," and this notion of life itself is principally characterized by what Foucault describes as the processes of circulation, flux, and flow. The problem of multiplicities is therefore also a problem concerning the government of the living, the governance, even, of "life itself." This is, to be sure, life understood as zoē and bíos, as biological life and the qualified life of the human being, but it must also be understood in terms of what Aristotle called psukhē—a principle of life, a vital principle, the Life of the living. [6] While human agency both individual and collective is implicated in this notion of life as psukhē, it is also an non-human, unhuman form of life—one that nevertheless courses through us and through which we live. Thus the primary challenge to biopolitical modes of power is this: how to acknowledge the fundamentally unhuman quality of life as circulation, flux, and flow, while also providing the conditions for its being governed and managed. Biopolitics in this sense becomes the governance of vital forces, and biopolitics confronts what is essentially a question of scale—how to modulate phenomena that are at once "above" and "below" the scale of the human being.

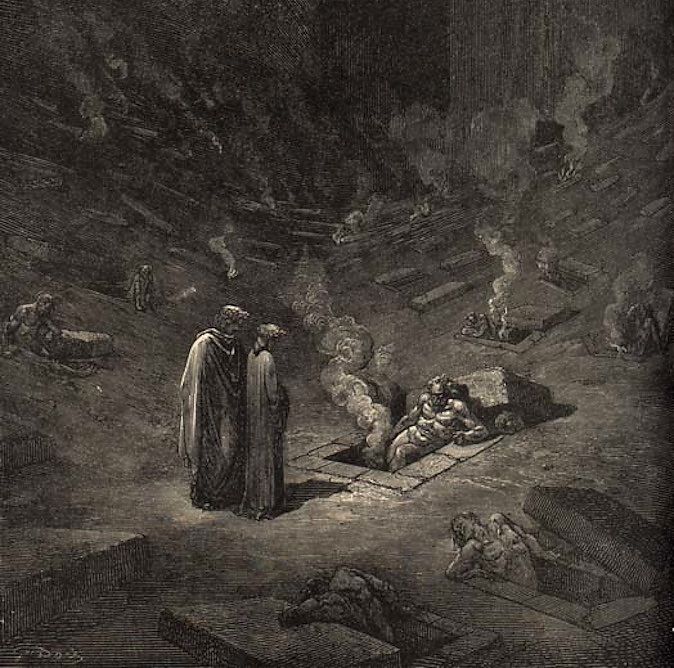

"L'Inferno" (Gustave Doré, 1857)

Poetics of Biopolitics. The classical term nekros encapsulates many dichotomies of the biopolitics concept. In its traditional sense, nekros names the corpse, the body that is no longer living. When, for example, Odysseus holds funeral rites for his deceased companions, it is the nekros that is cremated. But when Odysseus makes his way to the underworld, what he encounters is not simply the dead body or the corpse, but "the ghosts of the dead" (nekuōn kataethnēōtōn). [7] Here nekros names "the dead" as a form of life, one that resists any reliable distinction between the living being and the corpse. And this second type of nekros is also a collective, politicized form of life (ethnea nekrōn, the "nations of the dead").

Nowhere is this more effectively demonstrated than in Dante's Inferno, where we see stratifications of the living dead that are at once the product of divine punishment and, as such, are meticulously managed as massing or aggregate bodies. In the sixth circle, where Dante and his guide Virgil come up to the giant, fortress-like gates of the infernal City of Dis. Guarded by hordes of demons, Virgil must enlist divine intervention in order to pass through the gates. Once Dante and Virgil enter, what they see is a city in ruins, an uneven landscape of burning, open graves:

And then we started moving toward the city (terra)

in the safety of the holy words pronounced.

We entered there, and with no opposition.

And I, so anxious to investigate

the state of souls locked up in such a fortress (fortezza),

once in the place, allowed my eyes to wander,

and saw, in all directions spreading out,

a countryside (campagna) of pain and ugly anguish. [8]

In this landscape, at once terra, fortezza, and campagna, Dante and Virgil come to across another type of terrain—that of a landscape of open graves:

the sepulchers make all the land uneven,

so they did here, strewn in all directions,

except the graves here served a crueler purpose:

for scattered everywhere among the tombs

were flames that kept them glowing far more hot

than any iron an artisan might use.

Each tomb had its lid loose, pushed to one side,

and from within came forth such fierce laments

that I was sure inside were tortured souls. [9]

This harrowing vision of a field of burning graves blurs the boundary between corpse, grave, and the terrain itself. The scene prompts Dante to ask Virgil, "Master, what kind of shades are these lying down here, buried in the graves of stone, speaking their presence in such dolorous sighs?" His response: "There lie arch-heretics of every sect, with all of their disciples; more than you think are packed within these tombs." [10]

In Dante's version of the dead walking the earth, the living dead are explicitly ordered within the City of Dis; indeed, the living dead are the "citizens" of this city. Furthermore, as Virgil notes, the living dead are politicized: they are the heretics, those who have spoken against the theologico-political order, and, importantly, who have done so from within that order. In this way Dante links the heretics to the other circles of lower Hell, including the "sowers of discord" (who are meticulously, anatomically dismembered) and the "falsifiers" (who are ridden with plague and leprosy).

Nowhere else in the Inferno are we presented with such explicit analogies to the classical body politic. The City of Dis is, of course, very far from the idealized polis in Plato's Republic, or the civitas Dei described by Augustine. The City of Dis is not even a living, human city. Instead, what we have is a necropolis, a dead city populated by living graves, by the dead walking the earth. The City of Dis is, in this guise, an inverted polis, an inverted body politic.

Again we have the ambiguous vitalism of the "shades," as well as their massing and aggregate forms. But here the living dead are not simply an instance of judgment or divine retribution; in fact, they are the opposite, that which is produced through sovereign power. This sovereign power not only punishes (in the famous contrapasso), but, more importantly, it orders the multiplicity of bodies according to their transgressions or threats. In the Inferno, the living dead are not only a threat to political order, but the living dead are also organized and regulated by sovereign power. Sovereign power determines the living dead through an intervention into the natural workings of things, thereby managing the boundary between the natural and the supernatural. It does this not only to preserve the existing theological-political order, but also to identify a threat that originates from within the body politic.

Within this mortified body politic we witness two forms of power—a sovereign power that judges and punishes, but also a regulatory power that manages the flows and circulations of multiple bodies, their body parts and bodily fluids. In this way, Dante's underworld is utterly contemporary, for it suggests to us that the body politic concept is always confronted with this twofold challenge—the necessity of establishing a sovereign power in conjunction with the necessity of regulating and managing multiplicities.

Credits: This text is excerpted from an article originally published in the journal Incognetum Hacetenus, vol. 3 (2012), and reproduced here with the author's permission.

[1] Michel Foucault: The History of Sexuality. Vol. I: An Introduction. New York: Vintage 1990, p. 142.

[2] An important exception is the work of Roberto Esposito, whose trilogy Bíos, Immunitas, and Communitas examines the philosophical underpinnings of biopolitics as a concept.

[3] Michel Foucault: Sécurité, Territoire, Population. Cours Au Collège de France, 1977—1978. Paris: Gallimard/Seuil 2004, p. 16.

[4] Ibid., p. 12.

[5] Michel Foucault: Il Faut Défendre la Société. Cours Au Collège de France, 1976. Paris: Gallimard/Seuil 1997, p. 216.

[6] This idea is further explored in my book After Life. Chicago: University of Chicago Press 2010, pp. 1—24.

[7] The Odyssey. Trans. by Robert Fagles. New York: Penguin 1996, XI. 39.

[8] Inferno. Trans. by Mark Musa. New York: Penguin 2002, Canto IX, lines 104—111. Italian consulted at the Digital Dante Project.

[9] Ibid., 115—123.

[10] Ibid., 124—129.